Tag: history

Onward Octagon Ohio History: Cupola Chronicles, Happy Halloween!

Onward Octagon Ohio History: Cupola Chronicles

Welcome to Octagon Ohio History, brought to you from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio. Ashtabula County and all of Ohio has a fun and fascinating history, so let’s explore it together. Our view from the cupola gives us a bird’s eye view of the state and we can peek into all aspects of its history. Come along for an exciting history adventure!

Onward Octagon Ohio History: Cupola Chronicles, Ohio Ghosts Whisper to Us on Halloween

Welcome to Octagon Ohio History, brought to you from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio. Ashtabula County and all of Ohio has a fun and fascinating history, so let’s explore it together. Our view from the cupola gives us a bird’s eye view of the state and we can peek into all aspects of its history. Come along for an exciting history adventure!

Ghosts, goblins, ghouls, and other spooky minions of the worlds beyond our senses take center stage on Halloween, producing Halloween costumes, haunted houses, paranormal investigations, ghost tours and supersized paranormal parties and experiences.

Ohio Ghosts Whisper to Us on Halloween

We mortals are so busy celebrating and recreating the world of ghosts, imagining what they are like, and listening and looking for them in haunted houses that we really don’t hear them or their stories, not even in Ohio which is blessed with multitudes of multi-tasking and talented ghosts. For a moment, let’s stop and listen to some of

the tales of ghosts in Ohio who can be found in cemeteries, houses, hotels, seminaries, taverns, parks, libraries, and museums, just to name just a few haunted places.

Ghosts have to be approached with imaginations, the same imaginations that non believers in ghosts accuse believers of over actively using. Ghost stories are people and place stories. Ghost stories are created from people living everyday lives and leaving imprints in the ether of time and space after their mortal lives have moved on to other dimensions.

Cemetery Ghosts

During a blinding blizzard on December 29, 1876, the Lakeshore and Southern Michigan’s Pacific Express inched its way across a railroad trestle over the Ashtabula River gorge. One of the two engines reached the other side of the bridge, but when the bridge collapsed, the other engine and eleven cars tumbled into the gorge 1,000 feet below. Approximately 92 people perished from hypothermia, injuries from the collision, or from the fire ignited from the stoves and oil lamps used to heat and light the railroad cars.

Cemeteries are the logical places to listen to ghosts and learn history as well. Andrew Skarupa, once superintendent of Chestnut Grove Cemetery in Ashtabula, Ohio, experienced one of his other worldly encounters with the ghost of Charles Collins. Twenty-five of the approximately 92 victims of the Ashtabula train wreck, one of the major disasters of the Nineteenth Century, play important roles in the story.

The unrecognizable remains of twenty-five of the victims were buried in a mass grave in Chestnut Grove Cemetery, along with Charles Collins, the engineer and architect who had helped build the bridge over the Ashtabula River gorge. Lakeshore Railroad President Amasa Stone and Charles Collins had reluctantly agreed to build the bridge over the Ashtabula River gorge out of iron instead of the traditional and time-tested wood.

A coroner’s jury criticized the bridge design and alleged that a competent bridge engineer inspection would have pinpointed the design defects in the bridge, holding Charles Collins and Amasa Stone accountable for its failure. After the investigative jury heard his testimony, Charles Collins wended his way home and shot himself in the head. He is buried in Chestnut Grove Cemetery, just several feet from the mass grave of the Ashtabula disaster victims.

Unlike other cemetery visitors, Andrew Skarupa didn’t see Charles Collins pacing in front of the mass grave of the victims or report that he saw Collins burying his head in his hands and crying, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry,” over and over. But Andrew experienced his own ghost sightings, including a woman, and an old man who wore a top hat and searched for his grandson. Besides human ghosts, Andrew reported seeing a horse, a dog, and a chicken. He noted, “It was funny really. I had seen a few other ghosts, but to turn around and see a chicken, well let’s just say some people didn’t believe me!1

1“The Spirit of Halloween.” Ashtabula Star Beacon October 31, 2004, page 1.

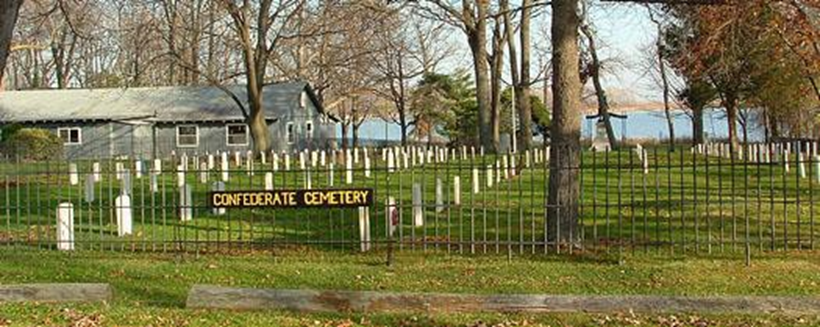

Johnson’s Island Confederate Cemetery

The United States government used Johnson’s Island, a 300-acre dot of land in the Sandusky Bay of Lake Erie and just three miles from the city of Sandusky, Ohio, as a Union prison. Originally the prison had been built for captured Confederate officers, but eventually all ranks of Confederate prisoners, political prisoners, and spies were imprisoned there during the Civil War. Tradition has it that 209 Confederate soldiers rest in the cemetery, but historical research suggests that the cemetery doesn’t contain all of the soldiers’ remains, but instead they are scattered around the island. Recent archaeological research indicates that over 100 additional unmarked graves can be found throughout the island.

Ghosts of Confederate soldiers, each with a life story, no matter how brief, wander Johnson’s Island and the cemetery is the stage for phantom battles, featuring gunshots, Rebel Yells, cries of the wounded, and the cadences of the marching feet of soldiers. Many participants swear that ghostly soldiers march along with their living comrades during the Memorial Day parades on Johnson’s Island. 2

His fellow laborers accidentally left an Italian woodcutter in the Confederate Cemetery stranded overnight when they took their boat back to Sandusky. Daunted but determined, he managed to build a fire and thank his good fortunado that he had some leftover sandwiches and beer from his lunch. He managed to collect enough leaves and branches to make a reasonably soft bed,

When he snugged into his makeshift bed and spread his jacket over him, the Italian woodcutter felt comfortable enough to wave goodnight to The Lookout and tell him to watch over the cemetery and over himself, the stranded woodcutter, while he slept. He stared at The Lookout, wondering about life in the South and the lives of the men he guarded. Had their dying thoughts been of home and family? Did they still think of home and want to be buried there instead of in this cold Northern cemetery? 2 “The Confederate Dead at Johnson’s Island. “Sandusky Daily Register, October 12, 1889, p. 2

At midnight, the Italian woodcutter awoke with a start and then he jumped from his comfortable branch bed, grabbed his coat, and ran down to the beach. He waved his coat and shrieked for help at the top of his voice. Later he swore to his rescuers who had finally realized that they had left him behind and came back for him, that The Lookout had turned his head several times surveying the cemetery. Then he had looked straight at the woodcutter shivering in his bed of boughs and leaves and winked!3

| Spooky Short Stories Germantown Cemetery Germantown, Ohio.A ghostly Civil War soldier rambles around the cemetery on a mission known only to him. |

3 The Daughters of the Confederacy, the Cincinnati Ohio Chapter, were instrumental in creating the state of The Lookout that guards the Johnson’s Island Confederate Cemetery. “The Confederate Dead at Johnson’s Island. “Sandusky Daily Register, October 12, 1889, p. 2

The Lady in Gray, Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery, Columbus, Ohio

Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery, Columbus, Ohio, is located on Livingston Avenue in Columbus, Ohio, Camp Chase served as a Confederate prison camp during the Civil War. Approximately, 2,000 prisoners died of disease and malnutrition at Camp Chase and many of them are buried in the prison cemetery.

The Lady in Gray, a young woman wearing a gray Civil War era traveling suit, walks though the cemetery, her head bowed and tears falling on the front of her suit. People have seen her making her way through the trees and out of the iron cemetery gates. No one has seen where she goes outside the gates.

Other cemetery visitors have reported fresh flowers appearing on the grave of an unknown soldier,

Civil War reenactors from 1988 reported hearing the sounds of a woman crying and some of them believe it is the Lady in Gray, still mourning a loved one.

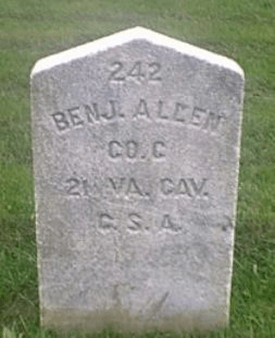

According to Cemetery records, two Confederate soldiers, both Benjamin Allens, sleep in the Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery. Benjamin Allen who was Pvt in Co .C of the 21st Virginia Cavalry of the Confederate States of America, was born on January 30, 1842, and died on September 15, 1864.

The other Benjamin is Benjamin F. Allen who was an infantry private in Co. D of the 50th Tennessee Regiment of the Confederate Army, born on March 18, 1844, in Stewart County, Tennessee, and died on September 8, 1864, at Camp Chase Prison Camp in Columbus, Ohio.

Some observers say that the Lady in Gray weeps in front of the grave of Infantry Private Benjamin F. Allen. What story will she tell to quiet listeners? Will it be about the ordeal of a long train ride from Tennessee north and once she arrived in Columbus, Ohio, a steady search for a hotel room and a friendly face? Or had she been notified of his grave condition before he died and rushed to his side to hold his hand and whisper comforting last words. Was she his sister? His sweetheart? Had they quarreled before he went to war or because he went to war? Her story shimmers in her tears, waiting to be told. AND, who weeps at the grave of the other Benjamin Allen of Company C of the 21st Virginia Cavalry? 4

The story goes that another cemetery ghost places fresh flowers on the grave of an unknown soldier in the Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery. More recently, someone discovered more contemporary plastic flowers on the grave. Time obscures the origin of the flowers, but the act of placing them on a soldier’s grave is as fresh as today and identifies the unknown soldier as honored and mourned.

| Spooky Short Stories Columbus, Ohio. Fort Hayes. The ghost of a young soldier killed in 1865 when he fired a cannon salute for the assassinated President Abraham Lincoln reportedly haunts Fort Hayes in Columbus. The overheated cannon exploded, killing the soldier.The story goes that his ghost still walks because he loved the fort commandant’s daughter and she supposedly knew the cannon would explode. |

4 Ghosts of Ohio, https://www.ghostsofohio.org/lore/ohio_lore_20.html ; Camp Chase Confederate Cemetery.

The Haunted Ohio Fog at Andersonville

Established on July 26, 1865, the Anderson National Cemetery works to preserve the graves of Union soldiers who died at Andersonville Military Prison. It is located 300 yards northwest of the prison site in southwestern Macon County, Georgia.

A Union prisoner at Andersonville (or Camp Sumter) faced favorable odds of dying and 13,000 Union prisoners of war did just that between 1861 and 1864. No weatherproof shelter existed at Andersonville, just crude tents that offered little protection from the wind, rain, heat or cold. A swamp running through the middle of the prison contributed to the squalid living conditions, including no latrines or clean drinking water, and rampant scurvy, diarrhea, and dysentery. The camp received few food supplies and many of the prisoners starved to death.

The human drama and suffering that took place at Andersonville prison were so indelibly imprinted on the 1860s air that modern visitors can hear the sounds of the prison and the voices of the men who lived and died there. Modern visitors hear the sounds of guns endlessly firing, shouting, whimpers, whispers. The wind blowing across the fields and through the endless rows of tombstones often carries cries of agony. Visitors have seen distinct human figures walking in the surrounding woods and fields and soldier shapes materializing from the fog that often blankets the prison site.

As visitors walk slowly among the tombstones of the National Cemetery at Andersonville, Georgia, some of the ghostly Ohio soldiers whisper identifying statistics.

- Edward Adams of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry, Company C, was captured at Hanover, Virginia on June 1, 1864. He died in Andersonville Prison on August 22, 1864.

- John Ditto of the 51st Ohio Infantry, of the 51st Ohio Infantry, Company A, was captured at Chickamauga on September 20, 1863. He died at Andersonville Prison on September 2, 1864.

- David C. Isham. 8th Ohio Infantry. He was captured at Chickamauga and died on February 4, 1865.

- William Radabaugh., Co. A. 33rd Ohio. He died on June 5, 1864 at age 25.

- Adam Spangler, Jr., Pvt. Co A, 45th Ohio. He died on May 20, 1864, at age 21.

- Lucius M. Wainright, Pvt. Co, G, 89th Ohio Infantry. He died on August 20, 1864 at age 21.

- Andrew J. Zink. Corp. Co. E, 72nd Ohio Infantry. He died on October 21, 1864.

Even though tombstone names, ranks, and other military statistics don’t reveal the human profiles of the ghosts or the contents of their characters or hearts, the personal suffering of the soldiers, their grief and despair that still linger over the Andersonville prison and settle like a wool blanket on the senses of modern visitors. raise important questions, especially this one: How could Americans treat other Americans so inhumanly, even with the excuse of war?5

Spooky Short Stories

In 1970, Andersonville prison and cemetery opened as a National Historical site and many visitors have reported hearing and seeing strange sights on foggy summer nights. The sightings had been reported ninety years before the site opened. One of the female visitors at the site reported talking to a ghost. As she walked through the grounds, she stopped in the middle of a hill to rest. She felt an unseen presence and couldn’t shake off the feeling that someone was watching her.

As she closed her eyes, she heard a voice, but when she looked around she didn’t see anyone. She closed her eyes again and she heard a voice in her head and it seemed to her the voice had something to tell her. “Were you a prisoner here? “Yes,” the voice said. “Did you die here?” she thought.

“Yes,” the voice answered. Before she left, the man told her his name, Andrew Zink, and she asked a staff person to look up Andrew Zink. The staff member found the soldier’s name, Andrew Zink, on the list of Ohio prisoners who had died at Andersonville.

5 Andersonville, prisoner details https://www.nps.gov/civilwar/search-prisoners-andersonville- detail.htm?prisonerId=66127249-1E81-46EA-99B0-125D1C5DA325

National Cemetery at Andersonville, Georgia https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/32522/andersonville-national- cemetery

Ghosts Around Town

In 1813, Ashtabula citizens started a subscription library with fewer than 100 books. Over the years as the Ashtabula population grew, so did the book list and the need for a designated library building. In 1896, the library was incorporated as the Ashtabula Free Public Library. Local officials used funds from the Andrew Carnegie Library program to construct the library building, located on West 44th Street, in 1903.

The years marched forward to 1953, and changes in the Ohio State law enabled the Ashtabula Free Public Library to become a county district library. Remodeling and expansion in 1958, 1984, 1991, and into the 2000s added a new entrance, elevators, and additional space for books computers, CDs, DVDs, and more people. A fire destroyed the second floor during the one- million-dollar remodeling project in October 1991, and during its 18-month relocation, a Chicago newspaper columnist wrote about the devastating fire. People and organizations nationwide donated over 30,000 books to the Ashtabula County District Library. The renovated building reopened in March 1992.

A photo in an Ashtabula Star Beacon story shows head librarian Ethel J. MacDowell and other employees at the Ashtabula County District Library during the 1930s. According to her employees, Ethel, who never married, fashioned her entire life around the library. Her fellow library workers Genevra Durco; Mildred—– ; Beulah May; Agnes Jean Neeley; Charlotte Chapman, Marian Covert (standing); Helen Saterlee;Nellie McDougall; and Elenor Hubbard pose for the photo.

Some ghost listeners and people who knew her believe that Ethel MacDowell has overseen the changes to her library even though she died on November 15, 1970, she and monitors the library closely from her portrait on the wall of the former Ohio Room. Some add the qualification that no, she only haunted the library from 1903, the year the building opened, until the October 1991 fire and renovation Her mission is to ensure that everything is right with her library world, and she still patrols the library to make sure everything is in order. 6

Ethel J. MacDowell’s death certificate shows that her birth date is September 27, 1882 and that she died on November 15, 1970 at age 88. She is buried in Lake Park Cemetery in Rocky River, Ohio. Ethel spent 45 of her life years at the Ashtabula County Library, working her way from assistant to head librarian. People who knew her said that Ethel focused on orderliness and accuracy and toiled to enforce them in the library, her fellow librarians, and to a lesser extent, the library patrons. She almost certainly enforced the standard finger- to- the- lips universal library SHHHHH!

In Ethel’s Ashtabula Library, patrons reported heavy footsteps creeping up antique stairs and apparitions and cold spots regularly occurring in the basement hallway. They said she haunted the old library building, dropping books and relocating book carts and rearranging shelves. She also communicated her opinions about changes in the library. Former Library Director William Tokarcyzk said that Ethel maneuvered her portrait in the Ohio Room to hang crooked when she disapproved of the changes that the library staff made in programs or in the rooms themselves. “It seems like we get more activity from her when we make a significant change such as a renovation or a change in a program which she may not approve,” he noted.

Former Assistant Library Director Donna Wall said that Ethel’s expression on her picture changes and her eyes followed people across the room depending on the happenings at the library and the behavior of the people inside. “No matter where you stand in there, she is looking at you. She is smiling today, but some days her lips are pursed and you know that she isn’t happy about something. “Both Bill and Dona said they didn’t feel threatened by Ethel’s ghost and they agreed that she adds character and mystery to the Ashtabula County Public Library.

| Spooky Short Stories Hinckley, Ohio. Built in 1845, the Hinckley Library served as the home of Vernon Stouffer of the Stouffer Food Company. After it was renovated as a public library in 1973, stories of ghostly sightings in the library circulated along with the library books. Patrons saw a ghostly man and woman on the stars, a workman encountered another ghostly figure in the basement and other people saw ghosts and felt cold spots throughout the library. Some people believe the ghosts are Dr. Nelson Wilcox and his sister Rebecca, who lived in a cabin located on the site before Vernon Stouffer built his house. |

6 “The Sprit of Halloween,” Ashtabula Star Beacon, October 31, 2004, p. 1, The Ashtabula District Library.”

The Madison Seminary

The Madison Seminary, on Middle Ridge Road in Madison, Ohio, is reportedly haunted by a boy named Steven whose father died in the Civil War. He and his mother moved to the Madison Seminary, which at the time served as a GAR home for the families of Civil War veterans.

In 1847, the Madison Seminary began as a small, wooden frame building on Middle Ridge Road in Madison, Ohio, and served students from 1847 until 1891. The Ohio Women’s Relief Corps, the Grand Army of the Republic’s auxiliary, purchased the seminary and on November 10, 1891, it officially became the Madison Home, with the purpose of assisting Army nurses and soldiers’ mothers, wives and sisters who had no means of support after the Civil War.

Through the years the building underwent transformations in style and use and in 1904, the Ohio Women’s Relief Corps donated the building to the State of Ohio because it could no longer to afford to maintain it. The state owned the building for several decades and it is privately owned in the 21st Century.

Observers at the GAR Home reported that besides seeing the ghostly boy Steven, they had also observed a woman step out of the closet and stare out the window. Some observers think that the ghostly woman could be Elizabeth Stiles. Elizabeth Stiles opened her eyes to the world in East Ashtabula, Ohio. Her life years between August 21, 1816 and February 14, 1898 took her to Illinois, Kansas and her spying missions for President Abraham Lincoln expanded her travels to other states. She spent the later years of her life with her adopted son and daughter in Fertigs, Pennsylvania and closed her eyes for the last time at the Woman’s Relief Corps home in Madison, Ohio, about ten miles from her birthplace in East Ashtabula.

Throughout her life, Elizabeth faced difficulties, danger, and heartbreak with a steadfast gaze and quick intelligence that enabled her to survive her husband’s murder, spying for the Union, and capture by a Confederate general. She died in the Woman’s Relief Corps home in July 18, 1898, and her family chose adjacent Madison Cemetery as her final resting place.

Some people question whether Elizabeth Stiles is truly resting, arguing that she is instead haunting the halls of Madison Seminary trying to warn modern people about the horrors of Civil War.

| Spooky Short Stories Ghost observers insist that the Wood County Historical Society Museum is haunted. The building served as the Wood County Poor House from 1900 to 1937, and later converted to a nursing home. Staff members experienced doors slamming, someone watching them, and one saw an old lady shuffling down the hallway and vanish. One part of the building served as an insane asylum, and staff members reported sounds of people scratching on doors and one saw a crying retarded boy looking out a window. |

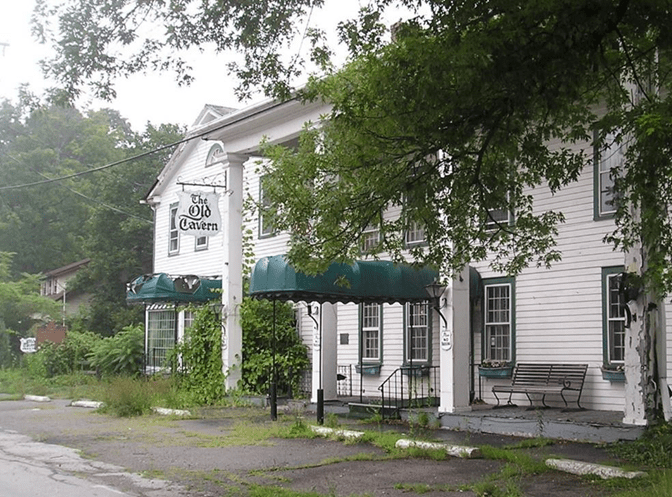

Ghosts of old Tavern, Unionville

Originally built as two separate log cabins in 1798 before Ohio became a state, the inn’s owners first called it the Webster House. Later, its name was changed to the New England House, the Old Tavern and finally, the Unionville Tavern, after its location in Unionville, Ohio.

Designated the first tavern in Ohio, the Old Tavern functioned as an oaisis for weary travelers navigating the Cleveland-Buffalo Road, present day Route 84, and a local spot for relaxation and revelry. Early settlers navigating the County Line Road in their covered wagons often stopped for rest and relaxation at the Old Tavern. By 1818, it had expanded to a stagecoach and mailstop on the Warren-Cleveland mail route and its owners had converted the cabins into a two-story saltbox style inn featuring a covered carriage entrance, an elegant parlor, and a ballroom.

The Old Tavern had become an active Underground Railroad Station by the mid-Nineteenth Century, with the first floor serving as a hideout for fugitive slaves on their way to Madison Dock and the passage across Lake Erie to freedom in Canada. The fugitives entered the entrance of a tunnel near the Southeast corner of the crossroads where the tavern stood. The tunnel took them under the tavern where they could stand upright and communicate with the innkeeper through a trap door. From the tunnel exit back of the tavern, the fugitive slaves were released or loaded on wagons bound for the Madison Dock and boats waiting to take them across the lake If they needed help on the last legs of their journey, they found protection and help at the homes of Amos and Cyrus Cunningham near Dock road in Madison.7

Recently, on summer nights, people gathered in the Old Tavern garden to listen to and tell ghost stories as part of a restoration of the tavern fund raising campaign. In the back of the crowd, shadows flicker across the lantern light and whispers of song penetrate the voices of the crowd. The whisper voices are singing, “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” and the whispers grow in volume to shouts as the shadows emerge from the tunnel and climb into the waiting wagon that will take them to Dock Road, Canada, and freedom.

7 From History of the Dock Road Arcola Creek Area Madison Township, Ohio 1796 – 1863 By: Sue Orris, Madison Historical Society August 9, 1980.

| Spooky Short StoriesT he “Our House” Tavern, built in 1819 and now a museum inGallipolis, Ohio, has the reputation of being haunted.Volunteers and visitors have reported invisible footsteps in the front hall and a woman singing in an empty ballroom on the second floor. |

| Spooky Short Stories The McConnelsville, Ohio, Opera House is considered to be one of the most haunted theaters in the state. Owners used the building as a stop on the Underground Railroad and renovations in the early 1960s w0ke up some ghosts. Workers reported an invisible woman singing and an equally invisible piano playing. |

Ghosts and Trains

Zaleski, Ohio

Moonville Tunnel

Over a century ago, Moonville, near Lake Hope State Park in Southeastern Ohio, was one of the many small towns that grew up around the booming iron furnace and coal mining industries.

Today, most are ghost towns, framed in overgrown foliage and crumbled scattered buildings and watched over by their resident ghosts. Moonville’s ghost is as old as the town. The Athens, Ohio messenger published the beginning of his story on November 10, 1880. The story said that Frank Lawhead, engineer on the Marietta & Cincinnati Railroad and the fireman, Charles Kreich were killed instantly when two freight trains ran together near Moonville on the eastern end of the railroad.

The accident happened when a dispatcher failed to notify the east bound train of an order to the west bound train to run on its own time. Both trains were totally wrecked. Shortly after the engineer and fireman were killed, a white ghostly form appeared along the tracks, frightening the engineers operating along the Cincinnati to Marietta route. They reported seeing a white figure swinging a lantern suddenly appear on the tracks.8

Fifteen years later, the Chillicothe Gazette chronicled the continuing pranks of the Moonville Ghost. The Gazette said that on a Monday night in February 1895 the ghost appeared in the railroad cut one half mile east of Moonville. Westbound fast freight No. 99, with engineer William Washburn at the throttle, was speeding along when he spotted the ghost wearing a pure white robe and carrying a lantern. The engineer reported that the ghost had a “flowing white beard, its eyes glistened like balls of fire, and a halo of twinkling stars surrounded it.”9

As the train approached, the ghost swung the lantern across the tracks, and then disappeared.Through the years, countless eyewitnesses also claim to have seen strange lights flitting around the Moonville tunnel in the patterns of a lantern swinging back and forth. Many who have walked the tunnel have felt chills surrounding them at the far end of the tunnel, producing goosebumps on their arms and hair standing up on the backs of their necks. A few have taken pictures of a ghostly man in an engineer hat walking across the tunnel.

8 Athens Messenger, Thursday, Nov 11, 1880

9 Chillicothe Gazette, February, 1895

Galion, Ohio. Ghostly trains can be heard approaching and passing the old Big Four Train Depot, with vibrations real enough to shake the building. There is a supposedly haunted room that locals call “the coffin room,” presided over by a man in a long coat. Others swear there is also an evil shadow entity lurking in the room.

Miamiville, Ohio. A railroad man killed during the Civil War is supposed to haunt the railroad tracks.

MIAMIVILLE is a little village on the left, grown up by the location of mills, and the construction of the Railway. MIAMI BRIDGE is about 18 miles from Cincinnati. Here the Railroad passes to the east side of the Miami, and continues on that side for fifty miles. The bridge is a substantial structure, –constructed for a double track-and above high water.

| Spooky Short Stories Arcadia, Ohio. A ghost lantern swimming back and forth over the tracks has stopped many trains passing through Weidler’s Passing Track near Arcadia. When the train stops for the brakeman to investigate, the light disappears into the woods. At other times, the light stays just ahead of the train and when it reaches Weidler’s, the light shoots into the sky. The light is believed to be the ghost of a railroad worker who died in a long-ago accident. |

Ghost Towns and Ghosts

The Quaker Ghost of Hambelton Mill

Beavercreek State Park, East Liverpool, Ohio. Sprucevale Trail in Beaver Creek State Park in Northeast Ohio is the site of a ghost town called Sprucevale, a once prosperous village.

In the mid-1800s Sprucevale had a post office, general store, woolen mill, grist mill, a blacksmith shop, and 17 houses. Today, the only evidence of its existence are the remaining three walls of Hambelton’s stone grist mill and the ghost of Quaker preacher Esther Hale.

One version of old mill haunting says that for nearly a century Esther Hale, a Quaker preacher dedicated to persuading people to follow her down the path to salvation, has haunted the old grist mill. Each year her ghost appears dressed in white and she writes her Quaker religious message on the wall of the old mill. Then she leads the way into the mill and disappears.10

The Watchman’s Ghost of the Iron Furnace

The remains of the iron furnace at Lake Hope State Park near Zaleski, Ohio, are the site of a ghost story. During the years the furnace operated as part of the iron mills and coal mine industries of Southeastern Ohio, the furnace had to be guarded day and night for fear that someone might fall into the molten iron. A watchman walked the ledge of the furnace, keeping a sharp eye on the furnace and an equally sharp eye for trespassers.

One stormy night around 8 p.m., as the watchman walked along the edge of the furnace with his lantern, lightning struck. The watchman fell into the hot molten iron. The iron furnace has long since been closed and its crumbling remains not sit along the lake at Lake Hope State Park.

Hikers have reported that during storms with severe lightning, they have seen the glow of a lantern and the silhouette of a watchman carrying a lantern walking around the ledge of the furnace.11

10 Medina County Gazette. October, 25, 1978. Mystery Shrouds Southeast Ohio with Sightings, Tales of Ghost

11 Medina County Gazette. October, 25, 1978. Mystery Shrouds Southeast Ohio with Sightings, Tales of Ghosts

Ghosts at Home

.Malabar Farm, Lucas, Ohio

The story goes that the Rose family had a plain daughter by the name of Ceely Rose, whose peers taunted her and made her life miserable. A farm boy felt sorry for Ceeley and befriended her, but Ceely mistook his friendly gesture for a proposal of marriage. When the embarrassed young man realized that Ceely truly expected a marriage, he told her that her family had asked him to stay away from her. Enraged, Ceely decided to kill her mother, father, and two brothers. She scraped arsenic from some fly paper and put it in her family’s cottage cheese.

A vacant white frame house stands near the main entrance of Louis Bromfield’s Malabar Farm home. A mysterious murder in the home owned by the Rose family, took place in the white frame house in 1896, and resulted in a haunting by a broken-hearted ghost.

The local sheriff eventually trapped Ceely into confessing that she had killed her family and she spent the rest of her life in a mental institution where she died at age 80.

Local residents have reported that on dark nights they have seen the face of a young girl pressed against the window pane of the vacant house. Could it be the ghost of Ceely Rose still searching her old house for her family and her never to be husband?

In 1939, Louis Bromfield an author and Hollywood celebrity bought the property where the Ceeley’s house stood and built a house and adjacent buildings, which he called Malabar Farm. A famous wedding took place at the Malabar farm in 1945, when Lauren Bacall and Humphrey Bogart were married there. Workers and visitors have reported flickering lights and ghostly sightings of Louis Bromfield at the farmhouse.12

12 Medina County Gazette. October, 25, 1978. Mystery Shrouds Southeast Ohio with Sightings, Tales of Ghosts

A Ghost Boy and His Ghost Dog

Dayton, Ohio

. Born in 1855, Johnny Morehouse was the youngest son of Barbara D. and John N. Morehouse and he lived with his parents in Dayton, Ohio in the back of his father’s shoe repair shop.

One day when he was five years old he went out to play near the Miami & Erie Canal and he fell into the water. His dog jumped into the water repeatedly trying to save him, but Johnny froze to death that day in 1860 when he fell into the Canal.

After his burial in Woodland Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio, the dog refused to leave Johnny’s grave, staying close to his young master even after he died. In 1861, Johnny’s parents had a special stone made to commemorate his dog’s devotion. His faithful dog and his toys adorn his tombstone. People have reported seeing them playing in the cemetery at night and the dog can be heard joyfully barking.

| Spooky Short Stories The ghost of Bessie Little is said to haunt the Ridge Street Bridge, Dayton. Her lover killed her and threw her into the Miami River. On quiet clear nights people have reported hearing her body splash into the River and then float above the surface. |

People Tell Ghost Stories

Migrating Tombstone

Rural Mount Union-Pleasant Valley Cemetery in Chillicothe contains “Elizabeth’s grave,” which has earned a certain amount of notoriety. Elizabeth’s headstone reportedly moves itself to the front of the cemetery after visitors move it to the back. Legend says she haunts the cemetery because she hanged herself from a nearby tree and she is unhappy with visitors moving her headstone.

Ghost Hill

Ghost or Cherry Hill is located on State Route 38, Yatesville-Wissler Road, Yatesville, Ohio. There are different versions of why local residents named the site “Ghost Hill.” One version goes that the spirit of a headless horseman stalks people along the roads and fields off State Route 38. This story says that the ghost was a federal agent that local innkeepers murdered because he interfered with their bootleg liquor trade. Another version of the story says that the headless horseman is the ghost of a man that thieves robbed and decapitated. When they went to pretend to discover his body, they couldn’t find it. He has been haunting the area since then, searching for his head.

Headless Civil War Soldier

Yellow Springs, Ohio. Charlie Batdorf, a Civil War soldier, is supposed to be responsible for a headless ghost haunting when several people have seen him walking up the path to his house.

Ghostly Couple

Eaton, Ohio. Eaton-Gettysburg Road. Several people have seen the ghosts of a soldier and his wife walking down the road holding hands. They have also been spotted under a large oak tree growing along the road. Legend has it that Indians killed his wife and drove a stake through her body near the oak tree.

Haunted Museum

Dayton, Ohio. The United States Air Force Museum is supposedly haunted by ghosts who appreciate the Air Force relics on display. Museum guards have reported objects moving by themselves, unexplained voices, and eerie sounds.

Owner Haunts Restaurant

The ghostly owner of The Village House Restaurant in Ashville, Ohio haunts his establishment and plays jokes to keep his staff members attention.

Ghosts Tell People Stories

The Ghosts and Old Peter

An anonymous ghost tells the people story of Old Peter Baines from the past. Old Peter lived alone on the outskirts of Taylorsville, Ohio, for over a decade. He believed more in ghosts than in people, including his neighbors. None of his neighbors paid much attention to Peter until he inherited $15,000 dollars from a family member.

Peter’s inheritance caused five of his neighbors to suddenly focus their feminine attention on Peter.

Miss Nancy Bebee, an old maid of nearly forty had never been married because gossip had it she had no money and no good looks to trade on the marriage market. Miss Prudence Higgins lived with the same circumstances. The Widow Henderson and the Widow Drew fared a little better because they had been comely enough to have married once, but they needed a few thousand dollars to endure their remarriages. Mrs. John White, while still married to a carpenter, had severe aristocratic tastes and not enough money to spend on them. Each of the five ladies created a ghost program agenda to carry out on Peter.

One midnight night before Peter had his inheritance in hand, a relative of Miss Nancy Bebee paid him a visit. He had been sleeping with his window open, so he heard a scratching on the casing. A hallow voice said, “Peter, Miss Nancy Bebee is very unhappy.”

What caused her unhappiness? Peter asked.

The ghost, who identified herself as the ghost of Miss Nancy Bebee’s dead mother, told Peter that he could relieve Miss Nancy’s unhappiness by give her $2,000 as soon as he received his inheritance. “She will marry and she will bless you. Fail not, Peter, lest the smallpox comes to you!” the motherly ghost admonished Peter as she glided away. Peter pledged the money.

On the second night, as Peter lay awake in his bed at midnight, he heard a soft rustling and a cold breeze blew in the window. A scary voice informed Peter that Prudence Higgins was a sad, sad girl who would possibly commit suicide and if she did so, Peter would be to blame. The voice told Peter that he could save the life of Prudence Higgins if he gave her $2,000 dollars. “Do it and live to be a hundred years old,” the ghost told Peter.

Peter told the ghost he would give Prudence the money and asked the ghost to identify itself. The ghost said it was the grandmother of Prudence Higgins and floated out over the pasture gate.

On the third night, Peter stayed awake, waiting for the ghost. The ghost arrived, telling Peter that grim death waited all around him. Peter told the ghost he wanted to live to be one hundred years old, and the ghost told him he would if he gave the Widow Drew $1,000 when he received his inheritance. Peter asked her if $100 would do and the ghost said, “Shall I beckon to death to come and enter this window?”

Peter promised the Widow Drew $1,000 and asked the identity of the ghost. The ghost said she was a gypsy woman who had been murdered. “Do not play me false,” she said as she climbed over the pasture fence. Peter thought he heard cloth ripping, but she had wriggled herself free and disappeared before he could get a closer look.

The next night Peter shut and nailed down the window, reasoning that his inheritance couldn’t afford any more visits from ghosts. When the fourth ghost appeared, announcing that he had to provide for the Widow Henderson or be haunted by evil spirits for the rest of his life, he resisted for a few moments. The persistent sighs and groans from the ghost and scratching on the window glass finally drove Peter to promise the Widow Henderson $1,500 in cash.

On the fifth night, Peter took some blankets and pillows and made his bed under the current bushes in the yard. Ghost number five appeared promptly at midnight, gliding toward his bedroom window. The ghost had pressed itself against the window when four other ghosts surrounded her. The five ghosts stared at each other for a moment, and then human voices began calling names. Human hands and feet moved and five ghosts clawed and scratched each other.

When the scrap had concluded, Peter crawled out of his nest under the current bushes. He discovered five badly torn and tattered bed sheets lying on the grass, along with combs, hairpins, and other ghostly belongings.

None of the ghosts returned to collect their belongings or the cash!13

The Intoxicated Cemetery Ghosts

Someone, maybe the ghosts themselves, had called Cleveland police to report a disturbance in the Lutheran Cemetery at 3 a.m. on a mid-May morning in 1939. When the police officers answering the call pulled up in front of the cemetery, a man ran in front of the car shouting, “There’s ghosts in Lutheran cemetery! I saw them, I tell you. I heard them talking and saw funny lights moving around.!”

Having made his alarming report, the man ran away, terror adding wings to his feet.

The police officers decided to investigate. They found an abandoned sedan at the cemetery gates which they discovered had been forced open. The police officers reasoned that ghosts don’t drive cars nor did they find it necessary to force cemetery gates open to enter or exit, so they were certain they were pursuing non-ghostly human beings. The policemen searched the cemetery, but found neither ghosts or humans, so they decided on a different strategy.

Patrolman Philip Huey, 318 pounds, hid behind a tombstone, while the other two officers left. Soon Patrolman Huey observed three heads emerging from behind three grave stones. Three bodies soon followed the heads, weaving like ghosts in the wind. Officer Huey wasn’t scared, because he had seen the weaving patterns in earlier cases. Officer Huey jumped from behind his tombstone, collared two women and a man, and called for his buddies.

The ghosts explained why they were in the cemetery. “We’re just visiting friends. What if it is three o’clock. What business is it of yours? This is a free country.”

Free county or ghost free country, the three were charged with intoxication.14

Like people, ghosts have the capacity for both good and evil and in-between actions. The ghost hunters who say they encounter evil spirits are likely telling the truth, but then there is the counter of Casper and his human equivalents. Perhaps the Halloween ghosts we see reflect our own personalities all year around.

13 “Ghosts Around.” Vanwert Daily Bulletin. August 10, 1910, page 4.

14 “Cemetery Ghosts Are Charged with Intoxication”. Elyria chronicle, May 13, 1939, page 1

Onward Octagon Ohio History: Cupola Chronicles, Getting to Know the Great Lakes

Getting to Know the Great Lakes

Deseronto, Ontario, Canada

Welcome to Octagon Ohio History, brought to you from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio. Ashtabula County and all of Ohio has a fun and fascinating history, so let’s explore it together. Our view from the cupola gives us a bird’s eye view of the state and we can peek into all aspects of its history. Come along for an exciting history adventure!

Queen Anne’s Communion Service

Mohawk native tribes had settled the Mohawk Valley in what later would become New York State long before Europeans arrived in the New World in the late 15th Century.

In the seventeenth century, the Jesuits and later missionaries from the Church of England introduced the Mohawks to Christianity. In 1710, a delegation of Mohawk chiefs traveled to the Court of Queen Anne in England with a special mission. They informed Queen Anne that they wished to become Christians and the Queen arranged for a chapel to be built for the Mohawk people at Fort Hunter in the Mohawk Valley in New York.

In 1712, the Queen gave them an eight-piece silver communion set for their new chapel.

After seventy years of peaceful Mohawk worship in the Chapel, the Revolutionary War broke out in the British Colonies in 1775. The Mohawk congregation buried the Queen Anne Communion set at Fort Hunter to keep it safe from looting. The Mohawks remained steadfastly Loyalist during the war, and when the Treaty of Paris ended it in 1783, they were angry and alarmed to discover that the new American government considered them Rebels and had made no arrangements to return their ancestral lands in New York to them.

Mohawk chiefs John Deserontyon, Joseph Brant, and other representatives from the Six Nations presented their case to Frederick Haldimand, Governor General of the Province of Quebec, who encouraged them to settle on Lake Ontario’s northern shore. Chief Brant chose to settle along the Grand River, but Chief Deserontyon and his people chose to relocate along the Bay of Quinte. Before he left the new United States, Chief Deserontyon returned to Fort Hunter and dug up the silver communion service.

On May 22, 1784, Chief Deseronto and about 100 Mohawks arrived west of the modern Deseronto and they held a flag raising ceremony and rededicated the silver communion service to their new country. Eventually, the pioneering Mohawk settlers built new churches and new communities, St. Paul’s in Brantford, and St. Georges in Tyendinaga. Meanwhile, the victorious Americans had used the Queen Anne Chapel as a tavern and stable. They eventually tore it down and used its stones to line the first Erie Canal. More spiritually minded Americans recovered a few of the stones and sent them to the two Anglican churches in Canada.

The wooden Anglican church built in 1784 and located in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory on the Bay of Quinte sheltered the silver communion service until a new brick church was built in 1843. A historical landmark sign on the original site, serves as a reminder of the collaboration between the British Crown, Ontario’s First Nations, and the Mohawk Loyalist emigres from the new United States of America.

The Mighty Mac

Ferries across the Straits of Mackinac separating Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsula had a capacity of about 462 cars per hour and it took them an hour to cross the Straits.

Designed by David Steinman and completed in November 1957, the “Mighty Mac” replaced the ferries that had operated since 1923.

Construction on the Mighty Mac began in 1954 and it is an amazing engineering accomplishment. David Steinman and his fellow bridge builders designed and built the bridge to withstand enormous ice pressure and to be absolutely stable even in hurricane force winds and storms that sweep the Straits of Mackinac. The Mighty Mac is a suspension bridge, five miles long. The outside lanes are 12 feet wide; the inside lanes are 11 feet wide; the center mall is two feet wide, and the catwalk, curb and rail width are three feet on each side, totaling 54 feet. The stiffening truss width in the suspended span is sixty-eight feet wide making it wider than the roadway it supports.

The one hundred millionth crossing of the bridge occurred on June 25, 1998.

November is the Cruelest Month

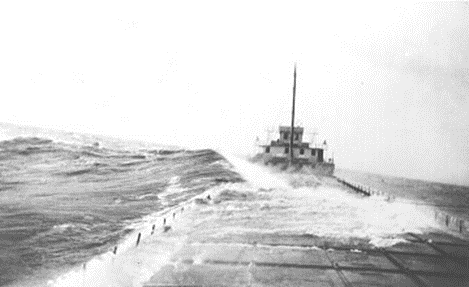

When cold Arctic winds start chilling the Great Lakes, skippers, mates, and ship hands yearn for the end of the shipping season and getting home before the big freeze.

But there is always one more run, just one more big load to make the season and collect that sizeable bonus.

Often in November when sudden storms and wintry ice work together, profit overpowers wisdom and the longing for home, and the captain sails into uncertain waters and races the weather. Savage autumn storms test all sections of a ship. A poorly balanced cargo, weak superstructure, unseen hull fractures…any flaw can be fatal. The fierce gales and wintry blasts of November quickly shred the canvas and shatter the masts. Hundreds of wooden ships and scores of steel ships rest in the icy deep, defeated by November on the Great Lakes.

The modern era of high safety standards, strict loading regulations, radar, and satellite weather forecasting greatly reduce November ship disasters, but ships that challenge November on the lakes still bet with risky odds.

Canoeing the Great Lakes

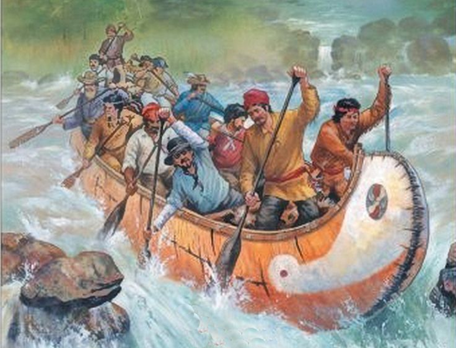

For nearly three hundred years, the simple birch bark canoe has shaped the history of the Great Lakes as an important transportation and practical commercial tool.

The Algonquin Indians were among the first tribes to use the birchbark canoes in what is now the northeastern United States and Canada. Birchbark canoes ranged from about 15 to 20 feet long to about one hundred feet long for some of the war canoes. The canoes carried goods, fishermen, hunters, and warriors. At times, twenty paddlers would navigate the war canoes.

Most Great Lakes Native American tribes were skilled birch bark canoe builders and operators. They used birch bark for the outer skin, reinforced it with cedar wood ribs sewn together with small roots of spruce trees, and sealed with pine gum. This method produced a strong and durable birch bark canoe.

French trappers, explorers, and missionaries valued these canoes as the most practical way of carrying supplies on rivers and creeks. Birch Bark canoes also encouraged them to eventually use the Great Lakes as highways. Canoes could navigate the streams and rivers threading their way through the vast timbered wilderness that separated Montreal from the western lakes and in time voyage from Lake Ontario all the way to Lake Superior.

Many French canoes measured over thirty feet long and often carried an eight-man crew. They could and often did carry a cargo of furs and provisions weighing over 6,000 pounds. The French and English settlers used these sturdy canoes well into the early 1800s.

Journey to Cathay(Now Known as China)

In 1634, Samuel de Champlain, Governor of New France, sent an expedition to the west with the goal of finding furs, charting unexplored land, and discovering a new route to the Orient, specifically Cathay (China). Expedition leader Jean Nicolet voyaged westward to the Lake Michigan shores, landing near Green Bay where Native Americans greeted him in a strange dialect. Believing he had reached China, Nicolet wore Oriental robes to greet what he believed were Chinese people.

Jean Nicolet soon discovered that the population was not Chinese, but residents of Winnebago Indian country, now Wisconsin. He had the background and experience to deal with the situation. Born in France, he had immigrated to Quebec and earned varied experience with Native American tribes. His experience included living with an Indian tribe on Allumette Island in the Ottawa River, learning the Algonquian language and culture and participating in negotiations with the Iroquois. Later he lived with the Nipissing tribe, eventually becoming their interpreter. In 1629, he went to the Three Rivers settlement in New France, becoming the colony’s official interpreter.

Early in 1634, Nicolet and his expedition embarked on their search for China.

They headed westward into Huron territory where he secured a large canoe and with seven Huron tribesmen, they padded down Lake Huron to the Straits of Mackinac into Lake Michigan and to Green Bay. Drawing on his extensive experience with Native American tribes, Jean Nicolet immediately took charge of the situation, arranging for future fur trade with the Winnebago and claiming the new territory for the French North American Empire.

Topky Brother’s , Ship’s Chandlers

W. Peerless, Superior, & Champion Mowers and Reapers, with all the latest improvements. For Sale by H.J. Topky.

Tiger Self-Operated Sulky Hay Rake, and Revolving Hay Rakes, for Sale by H.J. Topky.

Nuts, glass, hooks, latches, screws, bolts, hammers, planes, saws, hatchets, adzes, all carpenter’s tools and building materials, paints, oils, putty, turpentine, etc.etc. by H.J. Topky.

Ashtabula Telegraph

July 20, 1877

Oliver Topky later joined his father and brother John in operating the Topky hardware store in Ashtabula Harbor. Topky Hardware soon became a designated destination in Ashtabula city and township. An 1886 full page advertisement in the Marine Review of Cleveland shows that Topky operated as a ship chandler, a shop selling items for ships and boats, as well as a hardware store. After John died in 1898 and their father Henry Joseph Topky died in 1901, Oliver continued the business with the help of his staff. Mr. Topky finally retired from the hardware business in 1964.

The hardware store was a business when the harbor had a booming shipping trade. Goods were sold by the carload for use on the lake boats. As Mr. Topky recalled, only sailboats were able to enter the harbor and they were towed by tugs. Because the harbor was too shallow for steamboats, a tug had to go on before ships to dredge sand out of their path.

As a vintage Ashtabula Harbor businessman, Oliver Topky remembered many of Ashtabula’s firsts involving ships and railroads. He knew the names and stories of some of the first ships in the harbor, including the Tempest, the Ashtabula, Joshua R. Giddings, Arctic, Mary Collins, and Plow Boy. He could tell tales of the Great Lakes Engineering Company which launched the Steamer Louis R. Davidson in 1912, as its first ship in its Ashtabula yards.

Onward Octagon Ohio History: Cupola Chronicles, Axis Sally

Welcome to Octagon Ohio History, brought to you from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio. Ashtabula County and all of Ohio has a fun and fascinating history, so let’s explore it together. Our view from the cupola gives us a bird’s eye view of the state and we can peek into all aspects of its history. Come along for an exciting history adventure!

Axis Sally, Traitor, Troubled Soul, Or Both?

Mildred Sisk Gillars Kramer Gillars was the first woman to be convicted of treason against the United States. This is her prison photo from 1949.

Decades after her death in June 1988, the voice of Mildred Gillars still resonates in the lives and perceptions of 21st Century politics and in Conneaut history. A 2018 Smithsonian Magazine article by Jackie Manske pinpoints a Northwest Front podcast by American Neo-Nazi Harold Covington featuring a 21st century version of Axis Sally. The podcast portrayed Axis Sally as a courageous woman who defied Hitler and carved a successful career for herself, overcoming tremendous obstacles along the way.

Challenging the perspective of “successful career” are the five years that Mildred Gillars spent broadcasting propaganda for the Nazi Radio network as Axis Sally, urging American soldiers and sailors to give up the fight, and taunting them that their wives and girlfriends were at home flirting with 4F men or worse while they were homesick and risking their lives in battle.

Although she did not achieve the fame she craved as an actress, Mildred Gillars skillfully and successfully blended entertainment and propaganda that 21st media replicates. She used her musical talent in her Axis Sally broadcasts so well that the American soldiers listened to her just for her “great jazz.” She developed her reportedly sultry voice into an oratorical siren song that captured listeners even though they might hate her words and ideas.

Part of the story of Mildred Gillars unfolded in Conneaut. Although not a native of Conneaut, Mildred moved to Conneaut with her parents when she was a teenager, graduated from Conneaut High School, and married and spent a few more years in Ashtabula County before she attended Ohio Wesleyan University, moved to New York, and on to Europe and as much infamy as the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

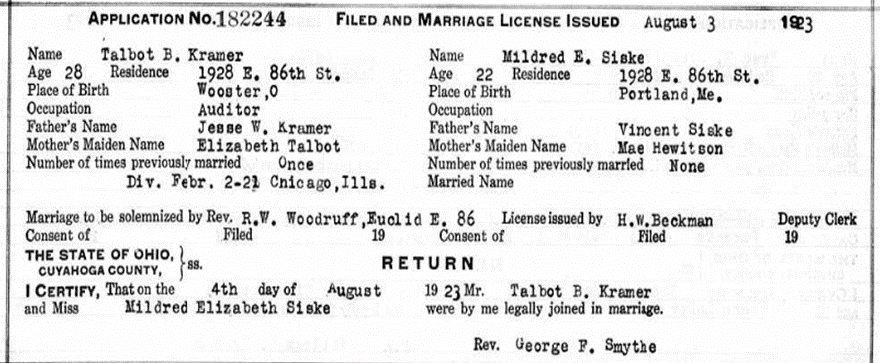

Different documents present varied statistics and interpretations of the Axis Sally story. Although even legal and census documents are not infallible, they are basic springboards to compare with differing versions of Mildred’s story. Vincent Sisk and Mary (Mae) Hewitson, both born in New Brunswick, Canada, were married on February 21, 1900, in Portland, Maine and Mildred Elizabeth Sisk was born on November 29, 1900, in Portland, Maine. Some of Mildred’s biographical sources state that her father Vincent Sisk was an abusive alcoholic and mistreated and then abandoned his wife and daughter. The records also reveal that Mildred’s sister Edna was born in 1909 and Robert Bruce Gillars is recorded as her father on the birth certificate. Mary and Vincent Sisk were divorced and Mary married Dr. Robert Brucie Gillars on July 20, 1914, in Huron, Ohio.

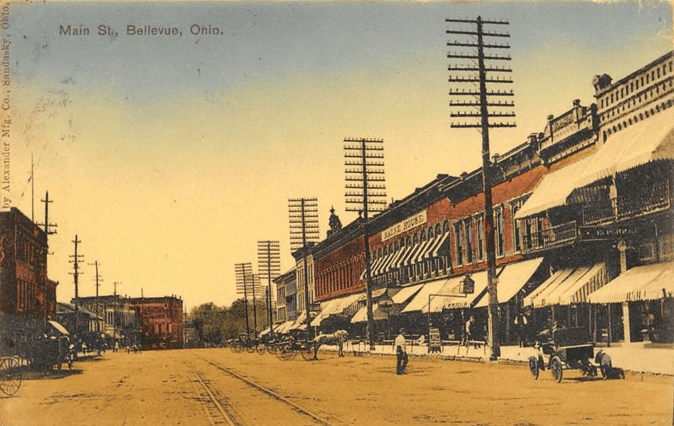

The 1910 Federal Census shows the Gillers family living in Bellevue, Sandusky County, Ohio.

In a 2011 article in the Columbus Dispatch, Joseph Blundo writes that the Gillars family moved to Conneaut in 2016 and Mildred graduated from Conneaut High School in either 1917 or 1918. The 1920 Federal Census records the Gillars living on Grant Street with Mildred listed as a member of the household.

Mildred spent her formative years developing an interest and a talent in music and the arts. Her biographer Richard Lucas interprets her childhood as filled with disfunction. John Bartlow Martin, a reporter covering her treason trial for McCall’s Magazine wrote that she “grew up in the unhappy home of a drunken, incestuous father,” referring to her stepfather Robert Bruce Gillars. Her desire for attention and validation and perhaps to escape the bleak reality of her life, motivated her to major in theater at Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware, Ohio. According to some sources, at Ohio Wesleyan she acquired the nickname Millie and played most of the available female dramatic leads copying the actress Theda Bara, an early silent film actress who introduced the sex symbol actress persona and ironically, had Ohio ties. She also excelled in oratory and flirting, with one source saying that she had numerous male but no female friends.

A former Wesleyan classmate noted that she wore her actress persona like a second skin, and that she worked hard to acquire a cosmopolitan personality that her upbringing had not provided her. The classmate said that she compulsively tried out for all of the plays and if a word or attitude fit the social patterns or norms, she would adopt them without really understanding them.

In 1922, during her senior year at Ohio Wesleyan, she suddenly dropped out, without graduating. Most narratives of her life story place her next move to New York City pursing her dream of acting on Broadway, but a Cuyahoga County marriage license stretches that time frame at least six years into the future.

The Cuyahoga County marriage license reveals that Mildred Siske,born in Portland, Maine, age 22, married Talbot Bergerman Kramer, age 28, on August 4, 1923.

The license stated that Mildred was the daughter of Vincent Siske and Mae Hewitson, revealing that Mildred took a short detour into marriage before she moved on to play her disastrous role in World War II Nazi propaganda.The documentary records also show that Talbot married Margarette R. Cullen in 1930, so Mildred and Talbot were divorced between 1923 and 1930.

If the accounts of her efforts to establish an acting career are correct, Mildred and Talbot Kramer’s marriage lasted for about three years, because they place Mildred performing as a chorus girl in 1926 Broadway musicals and going on to perform in comedies and vaudeville. To continue her Theda Bara sex symbol persona, she dyed her hair platinum blonde. She also enrolled in Hunter College and met Max Otto Kosciewitz, who would have an enormous impact on her life.

Over the next few years, Mildred traveled back and forth between Europe and the United States pursing her theatrical ambitions. In 1929, she lived in Paris for six months, and either in Paris or New York, she modeled for sculptor Mario Korbel. She spent the next few years working menial jobs, taking acting lessons, abd striving to gain recognition, but she could not manage to establish a stable career.

In 1933, Mildred moved to Algiers and found a job as assistant to a dressmaker. In 1934, she moved on to Dresden Germany to study music which would later significantly impact her career. After Dresden, she taught English in the Berlitz School for languages in Berlin, another move that would contribute to her future career.

Events in German and world history would profoundly impact Mildred’s personal life and career. An objective view of her early life shows that she based some of her adult choices on the male influences in her life. Established psychological tenets trace the influence of alcoholism and sexual abuse on the choices of abused children in their adult lives. After the divorce from Talbot Kramer, several other men influenced Mildred. While she still lived in New York, she became involved with a married Hunter College professor by the name of Max Otto Koischwitz. He had served in the German Foreign Office during World War I, and he spent years at Hunter College teaching the German language and German culture. They separated when she moved to Europe permanently in 1934.

When Mildred began her career with German State Radio in 1940 her broadcasts were mostly non-political. She was engaged to Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen. By 1941, the U.S. State Department advised American citizens to leave Germany and territories that Germany controlled. By 1941, the list of German controlled territories included Czechoslovakia, Poland, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Austria, Danzig, and parts of France and Italy as well as territories in Africa and a few of the English Channel Islands. In June 1941, Hitler launched the German invasion of the Soviet Union, called Operation Barbarossa. War clouds hung over the rest of the world, including the United States.

Most American nationals followed the State Department directive and left Germany. Mildred Gillars did not. Her fiancé Paul Karlson refused to marry her if she returned to the United States and she decided to remain in Germany. It took only a short time for Paul Karlson to be sent to the Eastern Front where he was killed in action. When Mildred refused to leave Germany, the State Department revoked her passport, which meant she could no longer travel. After Paul’s death, and especially after the United declared war on Germany on December 11, 1941, four days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Habor, Mildred feared that the Germans would put her in a concentration camp or perhaps even kill her. According to some versions of her story, her German employers forced her to sign an oath of allegiance to Hitler and Germany. She did so to protect herself and keep her job at the radio station.

In the meantime,22 Max Otto Koischwitz had returned to Germany after Hunter College had forced him to take a permanent leave because of his outspoken support of Nazi Germany and his anti-Semitism. The ideal candidate for German State Radio, he became the German-American program director in the USA Zone. Mildred Gillars and Max Otto Koischwitz resumed their affair and lived together in Berlin. He cast her in a new show called Home Sweet Home as well as including her in his political broadcasts. She no longer had to read bland copy and advertise mundane products. Following Max’s lead, Mildred began to express political opinions and anti-Semitic sentiments. “I say damn Roosevelt and Churchill, and all of their Jews who have made this war possible,” she asserted during one broadcast.

Mildred began to directly address American servicemen, telling them to give up the war and go home to reclaim their wives and sweethearts who were consorting with other men while they were gone. Her listeners were curious about her and asked her online to describe herself. She answered that she was “the Irish type, a real Sally.” Her GI audience gradually called her “Bitch of Berlin,” “Berlin Babe,” “Olga,” and “Sally.” In 1940, in a union dubbed the Axis Powers, Germany, Japan, and Italy had signed a pact defining their spheres of influence and agreeing to mutual miliary, political, and economic cooperation. Eventually, Mildred Gillars – Sally- became “Axis Sally.”

Even though Max Koischwitz scripted her broadcasts, ostensibly with the help of Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Propaganda Minister, Mildred as Axis Sally swung her broadcasting pendulum between playing the big band hits of the swing era, denouncing the Jews, Churchill, and Roosevelt, and urging GIs to give up fighting the war. After opening with an playing musical selections, (some sources say Lili Marlene was her theme song), she would say that she prided herself for telling “you American folks the truth and hope one day that you’ll wake up to the fact that you’re being duped; that the lives of the men you love are being sacrificed for the Jewish and British interests.”

Accounts of the reaction of American soldiers and the American home front listeners vary. Some soldiers eagerly awaited her programs because she played such “hot jazz.” Some thought her hilarious and entertaining. Others were angered by her propaganda and some secretly worried that what she said might really be the truth. Home front listeners were incensed that she implied that American women were unfaithful to their men overseas.

Mildred Gillars starred in three radio programs from 1942 to 1945. She broadcast in the Home Sweet Home Hour, from December 24, 1942, until 1945 with the goal of exploiting the worries of the American soldiers about the home front, encouraging doubts about their mission, their leaders, and their lives after the war. Opening with the sound of a train whistle, Axis Sally would speculate about the fidelity of the wives and sweethearts of the soldiers. She would pose the question of whether their wives and sweethearts would remain faithful, “especially if you boys get all mutilated and do not return in one piece.”

Midge at the Mike, broadcast from March to late fall 1943. In this program, Mildred/Midge played American songs and between them she wove in defeatist messages, anti-Semitic rants, and attacks on Franklin D. Roosevelt.

GI’s Letter box and Medical Reports, broadcast in 1944. These broadcasts were directed to the American audience at home and in them, Axis Sally used information about wounded and captured U.S. airmen that she and Max Koischwitz had gathered from interviewing them to bombard their families with fear and worry about them.

Axis Sally broadcast her most famous program on May 11, 1944, a few weeks before the real Allied landings on Normandy beaches. Max Koischwitz wrote a radio play that he called Vision of Invasion. Axis Sally played the part of Evelyn, an Ohio mother who dreamed that her son had been aboard a ship in the English Channel on the way to France and drowned during an invasion of Nazi occupied Europe.

In the play, Evelyn and Elmer, her husband, are at home in America talking while their son Allan is aboard an invasion boat on D-Day. Elmer is trying to convince Evelyn that her dream won’t come true. Evelyn replies: “But everybody says the invasion is suicide. The simplest person knows that. Between 70 and 90 percent of the boys will be killed or crippled for the rest of their lives.”

At another point Evelyn says to Elmer: “The whole world, waiting and watching for hundreds of thousands of young men to be slaughtered on the beaches of Europe and you — you laugh!” …

The broadcast closes with the background sound of church bells and Evelyn asking: “Why are those church bells ringing?”

Another woman answers, “The dead bells of Europe’s bombed cathedrals are tolling the death knell of America’s youth.”

For a time after D -Day, June 6, 1944, Mildred, and Max worked from Chartres and Paris visiting hospitals and camps in Germany. Claiming to be International Red Cross workers, they interviewed captured Americans, and recorded their messages to their families in the United States. Then they edited the interviews for broadcasts as if the interviewees were well treated or sympathetic to the Nazi cause. This touring and recording project that Max and Mildred did together did not last longer than a few months, because Max Koischwitz died in August 1944 of tuberculosis and heart disease.

Axis Sally’s broadcasts changed after Max Koischwitz died. Without his creative touch, they became dull and repetitive, probably reflecting Mildred’s state of mind and heart. She stayed in Berlin until the end of World War II, broadcasting her last Axis Sally program on May 6, 1945, two days before Germany surrendered.

For ten months after her last Axis Sally broadcast, Mildred struggled to survive and stay under the radar of the Americans. Now, her efforts to worry the GIs and the home front listeners dominated her own life. The Americans were looking for her and dodging them made her life a struggle.

On the orders of the U.S. Attorney General, prosecutor Victor C. Woerheide traveled to Berlin to find and arrest Axis Sally, Mildred Gillars. The prosecutor and Counterintelligence Corps special agent Hans Winzen had just one solid lead. POW Raymond Kurtz, a B-17 pilot that the Germans had shot down remembered that a woman had visited his prison camp looking to interview the prisoners had introduced herself as “Midge at the Mike.” She told him that she often used the alias Barbara Mome. Using that slender clue, Prosecutor Woerheide created wanted posters with Midge’s picture on them and circulated them all over Berlin. Finally a breakthrough came when an informer told him that a woman named Barbara Mome was selling her furniture in second hand markets all over Berlin. One shop owner had purchased a table from Axis Sally, and after some intense interrogation by the Americans he gave them her address. When she was arrested on March 15, 1946, Axis Sally wanted only to take a picture of Max Otto Koischwitz with her to prison.

The American Counterintelligence Corps held Mildred Gillars at Camp King, Oberursel, Germany, until they conditionally released her on Christmas Eve, 1945. She declined to leave military detention. The United States Justice Department abruptly rearrested her on January 22, 1947, and after detaining her for a year in Frankfort without charging her with any crime, they flew her to the United States on August 21, 1948, to stand trial on charges of aiding the German War effort. She was indicted on September 10, 1948, and charged with ten counts of treason. When her trial began on January 25, 1949, in Washington D.C., prosecutors used just eight of the indictments, focusing their main argument for conviction on the numbers of propaganda programs that the Federal Communications Commission had recorded and her participation in the activities against the United States. The Communications Commission also had evidence that Mildred Gillars had signed an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler. The prosecution also presented testimonies of soldiers and sailors whose stories she had written under false pretenses and twisted for propaganda purposes.

The defense contended that she stated unpopular opinions in her broadcasts, but they did not add up to treason. They also argued that she had been under the influence of Max Otto Koischwitz, and not responsible for her actions until after he died.

Mildred appeared at her trial with a bouquet of bright red roses accenting her less colorful clothing and a black bow tying back her long silver hair. Her attire and attitude resembled a Hollywood premiere instead of a trial for treason. Radio broadcasters and newspaper and magazine reporters from the United States and abroad converged on her trial, including McCall’s and Time Magazine. The Time Magazine reporter covering the trial expressed the popular scorn of the Defenses’ contention that Mildred acted under the influence of Max Koischwitz.

“Little Miss Echo. She described him as a man “who loved the mountains [of Silesia] with the intensity that a man might love a woman.” In 1943 he went there to think about Miss Gillars (he had a wife and three children) and there found that “God favored his love.” After that, she echoed his ideas like an empty barrel on a hog caller’s porch.”

People probably reacted more strongly to Mildred when the prosecution asked her about her relationship with Max Kioschwitz. The Time Magazine reporter wrote, “Miss Gillars lowered her eyes, breathed heavily, and said, “It is difficult to discuss … It is like discussing religion.” But finally, tossing her long silver-grey hair, she admitted, “Of course I loved him.” She added: “I consider Professor Koischwitz to have been my destiny . . .”

On March 10, 1949, the jury found Mildred Gillars guilty of just one count of treason, her action in making the Vision of Invasion broadcast. The judge sentenced her to ten to thirty years in prison, a $10,000 fine in 1949 dollars, with the stipulation of eligibility for parole after ten years in prison. The judge did not impose a harsher sentence since there was no proof that she had taken part in high level Nazi propaganda policy conferences like other American collaborators. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia upheld her conviction in 1950.

Mildred Gillars served her sentence at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, becoming eligible for parole in 1959. She did not apply for parole until 1961, and she was released on June 10, 1961. While serving her prison time, Mildred had converted to Catholicism, and after her release she went to live at the Our Lady of Bethlehem Convent in Columbus, Ohio. The church operated St. Joseph Academy where she taught German, French, and Music. Fifty-one years later in 1973, she returned to Ohio Wesleyan University and completed her degree, earning a Bachelor of Arts in speech.

On June 25, 1988, Mildred Gillars died of colon cancer at Grant Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio.

She is buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Lockbourne, Franklin County, Ohio.

Mildred’s mother, step father and half sister are buried in Glenwood Cemetery, in Conneaut. Mary (Mae) E. Gillars died in March 1947/

Thirty-six years after her death, the life of Mildred Gillars is still controversial and still resonates in today’s pollical and social climates. Writer and short-wave radio enthusiast Richard Lucas believes that Mildred Gillars was neither totally a traitor to her country nor totally innocent in her choices. “I was really trying to have a nuanced story of her and make her seem like a human being rather than a caricature,” says Richard Lucas. “Especially today. People are not black and white; there are all kinds of tradeoffs that lead them to become who they are.”

Was she a premediated traitor who had a deep-seated, long-lasting hatred of America and its ideals or was she a situational traitor with an overpowering need for attention and validation, who made poor choices of men and based her decisions on her feelings for them instead of moral and patriotic reasons?

Sources

Axis Sally Brought Hot Jazz to the Nazi Propaganda Machine. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/axis-sally-and-art-propaganda-180970327/

“TREASON: True to the Red, White & Blue”. Time. March 7, 1949.

Joseph Blundo. Sally’s Axis of Evil Ended at Convent in Columbus. Columbus Dispatch, archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

Le Bijou, yearbook of Ohio Wesleyan University, 1922.

Records, Ancestry.com

Find a Grave, Mildred Gillars

Richard Lucas. Axis Sally, the American Voice of Nazi Germany. Casemate, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010.

Example of Axis Sally’s Hot Jazz

The Kent Stater, Volume XXIII, Number 32, 25 November 1947. “let’s Face It, Democracy Takes a Beating. https://dks. library.kent.edu.?

Saturday Evening Post Digital Archive – Axis Sally https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46F25mtF8kg

Gillars’ wartime broadcasts and trial : the 2021 legal drama American Traitor: The Trial of Axis Sally

Onward Octagon Ohio History: Cupola Chronicles, Elizabeth Stiles

Welcome to Cupola Chronicles, brought to you from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio. Ashtabula County and all of Ohio has a fascinating and fun history so let’s explore it together! Our view from the cupola gives us a bird’s eye view of our state and we can peek into all aspects of its history. Come along for an exciting history adventure!

Elizabeth Stiles, President Abraham Lincoln’s Spy

Elizabeth Stiles opened her eyes to the world in East Ashtabula, Ohio. Her life years between August 21, 1816, and February 14, 1898, took her to Illinois, Kansas and her spying missions for President Abraham Lincoln expanded her travels to other states.

She spent the later years of her life with her adopted son and daughter in Fertigs, Pennsylvania and closed her eyes for the last time at the Woman’s Relief Corps home in Madison, Ohio, about ten miles from her birthplace in East Ashtabula.

Throughout her life, Elizabeth faced difficulties, danger, and heartbreak with a steadfast gaze and quick intelligence that enabled her to survive her husband’s murder, spying for the Union, and capture by a Confederate general.

Ashtabula and Elizabeth Stiles

When Elizabeth greeted the world on August 21, 1816, her mother Clarissa, and father John Fox Brown, and her brother John Jones Brown were new settlers in East Ashtabula, situated on the east bank of the Ashtabula River.

Elizabeth’s father, John Fox Brown and her mother Clarissa Chamberlain Brown hailed from Middleton, Connecticut, and her brother, John Jones Brown, was born in Middletown, Connecticut in 1813.

Elizabeth was born in Ashtabula in 1816, and her younger sister Emeline in 1828, also in Ashtabula. Ashtabula and Elizabeth Stiles grew up together. East and West Ashtabula on both sides of the Ashtabula River and the few houses at the harbor where the river flowed into Lake Erie made up early Ashtabula.

The rivalry between East and West Ashtabula began almost as soon as the first settlers climbed wearily down from their wagons or beached their boats on the Ashtabula Riverbank.

Thick stands of oak, maple, and hemlock trees canopied the fertile soil and snow buried the trees under a white blanket in winter. The early settles quickly set to work cutting down the trees for wood to build their houses, barns, and businesses. Soon, log houses punctuated the forests like the quilt squares the pioneer women piecedand gardens and fields of corn and other crops provided quilted backing for the landscape.

Many people could not see the smoke rising from their neighbor’s chimneys above the trees, because their log houses were so far apart with frame barns behind just a few of them. Roads not much wider than a horse and wagon snaked around the trees. Both trails and roads led to the taverns located in all three of the settlements.