Cupola Chronicles from the David Cummins Octagon House- Conneaut, Ohio

Welcome to our first Cupola Chronicle from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio! Ashtabula County and in fact, all of Ohio contains more fascinating historical stories about people, places, and things than Lake Erie does waves, so we will use the cupola from the top of our Octagon House as a crow’s nest to see and spread the stories to sailors , shore people, and anyone else who enjoys history.

Axis Sally: Traitor, Troubled Soul, or Both?

Mildred Sisk Gillars Kramer Gillars was the first woman to be convicted of treason against the United States. This is her prison photo from 1949.

Decades after her death in June 1988, the voice of Mildred Gillars still resonates in the lives and perceptions of 21st Century politics and in American history. A 2018 Smithsonian Magazine article by Jackie Manske pinpoints a Northwest Front podcast by American Neo-Nazi Harold Covington featuring a 21st century version of Axis Sally. The podcast portrayed Axis Sally as a courageous woman who defied Hitler and carved a successful career for herself, overcoming tremendous obstacles along the way.

Challenging the perspective of “successful career” are the five years that Mildred Gillars spent broadcasting propaganda for the Nazi Radio network as Axis Sally, urging American soldiers and sailors to give up the fight, and taunting them that their wives and girlfriends were at home flirting with 4F men or worse while they were homesick and risking their lives in battle.

Although she did not achieve the fame she craved as an actress, Mildred Gillars skillfully and successfully blended entertainment and propaganda that 21st media replicates. She used her musical talent in her Axis Sally broadcasts so well that the American soldiers listened to her just for her “great jazz.” She developed her reportedly sultry voice into an oratorical siren song that captured listeners even though they might hate her words and ideas.

Part of the story of Mildred Gillars unfolded in Conneaut. Although not a native of Conneaut, Mildred moved to Conneaut with her parents when she was a teenager, graduated from Conneaut High School, and married and spent a few more years in Ashtabula County before she attended Ohio Wesleyan University, moved to New York, and on to Europe and as much infamy as the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

Different documents present varied statistics and interpretations of the Axis Sally story. Although even legal and census documents are not infallible, they are basic springboards to compare with differing versions of Mildred’s story. Vincent Sisk and Mary (Mae) Hewitson, both born in New Brunswick, Canada, were married on February 21, 1900, in Portland, Maine and Mildred Elizabeth Sisk was born on November 29, 1900, in Portland, Maine. Some of Mildred’s biographical sources state that her father Vincent Sisk was an abusive alcoholic and mistreated and then abandoned his wife and daughter. The records also reveal that Mildred’s sister Edna was born in 1909 and Robert Bruce Gillars is recorded as her father on the birth certificate. Mary and Vincent Sisk were divorced and Mary married Dr. Robert Brucie Gillars on July 20, 1914, in Huron, Ohio.

The 1910 Federal Census shows the Gillers family living in Bellevue, Sandusky County, Ohio. In a 2011 article in the Columbus Dispatch, Joseph Blundo writes that the Gillars family moved to Conneaut in 2016 and Mildred graduated from Conneaut High School in either 1917 or 1918. The 1920 Federal Census records the Gillars living on Grant Street with Mildred listed as a member of the household.

Mildred spent her formative years developing an interest and a talent in music and the arts. Her biographer Richard Lucas interprets her childhood as filled with disfunction. John Bartlow Martin, a reporter covering her treason trial for McCall’s Magazine wrote that she “grew up in the unhappy home of a drunken, incestuous father,” referring to her stepfather Robert Bruce Gillars. Her desire for attention and validation and perhaps to escape the bleak reality of her life, motivated her to major in theater at Ohio Wesleyan University in Delaware, Ohio.

According to some sources, at Ohio Wesleyan she acquired the nickname Millie and played most of the available female dramatic leads copying the actress Theda Bara, an early silent film actress who introduced the sex symbol actress persona and ironically, had Ohio ties. She also excelled in oratory and flirting, with one source saying that she had numerous male but no female friends.

A former Wesleyan classmate noted that she wore her actress persona like a second skin, and that she worked hard to acquire a cosmopolitan personality that her upbringing had not provided her. The classmate said that she compulsively tried out for all of the plays and if a word or attitude fit the social patterns or norms, she would adopt them without really understanding them.

In 1922, during her senior year at Ohio Wesleyan, she suddenly dropped out, without graduating. Most narratives of her life story place her next move to New York City pursing her dream of acting on Broadway, but a Cuyahoga County marriage license stretches that time frame at least six years into the future.

The Cuyahoga County marriage license reveals that Mildred Siske,born in Portland, Maine, age 22, married Talbot Bergerman Kramer, age 28, on August 4, 1923. The license stated that Mildred was the daughter of Vincent Siske and Mae Hewitson, revealing that Mildred took a short detour into marriage before she moved on to play her disastrous role in World War II Nazi propaganda.

The documentary records also show that Talbot married Margarette R. Cullen in 1930, so Mildred and Talbot were divorced between 1923 and 1930.

If the accounts of her efforts to establish an acting career are correct, Mildred and Talbot Kramer’s marriage lasted for about three years, because they place Mildred performing as a chorus girl in 1926 Broadway musicals and going on to perform in comedies and vaudeville. To continue her Theda Bara sex symbol persona, she dyed her hair platinum blonde. She also enrolled in Hunter College and met Max Otto Kosciewitz, who would have an enormous impact on her life.

Over the next few years, Mildred traveled back and forth between Europe and the United States pursing her theatrical ambitions. In 1929, she lived in Paris for six months, and either in Paris or New York, she modeled for sculptor Mario Korbel. She spent the next few years working menial jobs, taking acting lessons, abd striving to gain recognition, but she could not manage to establish a stable career.

In 1933, Mildred moved to Algiers and found a job as assistant to a dressmaker. In 1934, she moved on to Dresden Germany to study music which would later significantly impact her career. After Dresden, she taught English in the Berlitz School for languages in Berlin, another move that would contribute to her future career.

Events in German and world history would profoundly impact Mildred’s personal life and career. An objective view of her early life shows that she based some of her adult choices on the male influences in her life. Established psychological tenets trace the influence of alcoholism and sexual abuse on the choices of abused children in their adult lives. After the divorce from Talbot Kramer, several other men influenced Mildred. While she still lived in New York, she became involved with a married Hunter College professor by the name of Max Otto Koischwitz. He had served in the German Foreign Office during World War I, and he spent years at Hunter College teaching the German language and German culture. They separated when she moved to Europe permanently in 1934.

When Mildred began her career with German State Radio in 1940 her broadcasts were mostly non-political. She was engaged to Paul Karlson, a naturalized German citizen. By 1941, the U.S. State Department advised American citizens to leave Germany and territories that Germany controlled. By 1941, the list of German controlled territories included Czechoslovakia, Poland, Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, Austria, Danzig, and parts of France and Italy as well as territories in Africa and a few of the English Channel Islands. In June 1941, Hitler launched the German invasion of the Soviet Union, called Operation Barbarossa. War clouds hung over the rest of the world, including the United States.

Most American nationals followed the State Department directive and left Germany. Mildred Gillars did not. Her fiancé Paul Karlson refused to marry her if she returned to the United States and she decided to remain in Germany. It took only a short time for Paul Karlson to be sent to the Eastern Front where he was killed in action. When Mildred refused to leave Germany, the State Department revoked her passport, which meant she could no longer travel. After Paul’s death, and especially after the United declared war on Germany on December 11, 1941, four days after the Japanese attacked Pearl Habor, Mildred feared that the Germans would put her in a concentration camp or perhaps even kill her. According to some versions of her story, her German employers forced her to sign an oath of allegiance to Hitler and Germany. She did so to protect herself and keep her job at the radio station.

In the meantime,22 Max Otto Koischwitz had returned to Germany after Hunter College had forced him to take a permanent leave because of his outspoken support of Nazi Germany and his anti-Semitism. The ideal candidate for German State Radio, he became the German-American program director in the USA Zone. Mildred Gillars and Max Otto Koischwitz resumed their affair and lived together in Berlin. He cast her in a new show called Home Sweet Home as well as including her in his political broadcasts. She no longer had to read bland copy and advertise mundane products. Following Max’s lead, Mildred began to express political opinions and anti-Semitic sentiments. “I say damn Roosevelt and Churchill, and all of their Jews who have made this war possible,” she asserted during one broadcast.

Mildred began to directly address American servicemen, telling them to give up the war and go home to reclaim their wives and sweethearts who were consorting with other men while they were gone. Her listeners were curious about her and asked her online to describe herself. She answered that she was “the Irish type, a real Sally.” Her GI audience gradually called her “Bitch of Berlin,” “Berlin Babe,” “Olga,” and “Sally.” In 1940, in a union dubbed the Axis Powers, Germany, Japan, and Italy had signed a pact defining their spheres of influence and agreeing to mutual miliary, political, and economic cooperation. Eventually, Mildred Gillars – Sally- became “Axis Sally.”

Even though Max Koischwitz scripted her broadcasts, ostensibly with the help of Joseph Goebbels, Nazi Propaganda Minister, Mildred as Axis Sally swung her broadcasting pendulum between playing the big band hits of the swing era, denouncing the Jews, Churchill, and Roosevelt, and urging GIs to give up fighting the war. After opening with an playing musical selections, (some sources say Lili Marlene was her theme song), she would say that she prided herself for telling “you American folks the truth and hope one day that you’ll wake up to the fact that you’re being duped; that the lives of the men you love are being sacrificed for the Jewish and British interests.”

Accounts of the reaction of American soldiers and the American home front listeners vary. Some soldiers eagerly awaited her programs because she played such “hot jazz.” Some thought her hilarious and entertaining. Others were angered by her propaganda and some secretly worried that what she said might really be the truth. Home front listeners were incensed that she implied that American women were unfaithful to their men overseas.

Mildred Gillars starred in three radio programs from 1942 to 1945. She broadcast in the Home Sweet Home Hour, from December 24, 1942, until 1945 with the goal of exploiting the worries of the American soldiers about the home front, encouraging doubts about their mission, their leaders, and their lives after the war. Opening with the sound of a train whistle, Axis Sally would speculate about the fidelity of the wives and sweethearts of the soldiers. She would pose the question of whether their wives and sweethearts would remain faithful, “especially if you boys get all mutilated and do not return in one piece.”

Midge at the Mike, broadcast from March to late fall 1943. In this program, Mildred/Midge played American songs and between them she wove in defeatist messages, anti-Semitic rants, and attacks on Franklin D. Roosevelt.

GI’s Letter box and Medical Reports, broadcast in 1944. These broadcasts were directed to the American audience at home and in them, Axis Sally used information about wounded and captured U.S. airmen that she and Max Koischwitz had gathered from interviewing them to bombard their families with fear and worry about them.

Axis Sally broadcast her most famous program on May 11, 1944, a few weeks before the real Allied landings on Normandy beaches. Max Koischwitz wrote a radio play that he called Vision of Invasion. Axis Sally played the part of Evelyn, an Ohio mother who dreamed that her son had been aboard a ship in the English Channel on the way to France and drowned during an invasion of Nazi occupied Europe.

In the play, Evelyn and Elmer, her husband, are at home in America talking while their son Allan is aboard an invasion boat on D-Day. Elmer is trying to convince Evelyn that her dream won’t come true. Evelyn replies: “But everybody says the invasion is suicide. The simplest person knows that. Between 70 and 90 percent of the boys will be killed or crippled for the rest of their lives.”

At another point Evelyn says to Elmer: “The whole world, waiting and watching for hundreds of thousands of young men to be slaughtered on the beaches of Europe and you — you laugh!” …

The broadcast closes with the background sound of church bells and Evelyn asking: “Why are those church bells ringing?”

Another woman answers, “The dead bells of Europe’s bombed cathedrals are tolling the death knell of America’s youth.”

For a time after D -Day, June 6, 1944, Mildred, and Max worked from Chartres and Paris visiting hospitals and camps in Germany. Claiming to be International Red Cross workers, they interviewed captured Americans, and recorded their messages to their families in the United States. Then they edited the interviews for broadcasts as if the interviewees were well treated or sympathetic to the Nazi cause. This touring and recording project that Max and Mildred did together did not last longer than a few months, because Max Koischwitz died in August 1944 of tuberculosis and heart disease.

Axis Sally’s broadcasts changed after Max Koischwitz died. Without his creative touch, they became dull and repetitive, probably reflecting Mildred’s state of mind and heart. She stayed in Berlin until the end of World War II, broadcasting her last Axis Sally program on May 6, 1945, two days before Germany surrendered.

For ten months after her last Axis Sally broadcast, Mildred struggled to survive and stay under the radar of the Americans. Now, her efforts to worry the GIs and the home front listeners dominated her own life. The Americans were looking for her and dodging them made her life a struggle.

On the orders of the U.S. Attorney General, prosecutor Victor C. Woerheide traveled to Berlin to find and arrest Axis Sally, Mildred Gillars. The prosecutor and Counterintelligence Corps special agent Hans Winzen had just one solid lead. POW Raymond Kurtz, a B-17 pilot that the Germans had shot down remembered that a woman had visited his prison camp looking to interview the prisoners had introduced herself as “Midge at the Mike.” She told him that she often used the alias Barbara Mome. Using that slender clue, Prosecutor Woerheide created wanted posters with Midge’s picture on them and circulated them all over Berlin. Finally a breakthrough came when an informer told him that a woman named Barbara Mome was selling her furniture in second hand markets all over Berlin. One shop owner had purchased a table from Axis Sally, and after some intense interrogation by the Americans he gave them her address. When she was arrested on March 15, 1946, Axis Sally wanted only to take a picture of Max Otto Koischwitz with her to prison.

The American Counterintelligence Corps held Mildred Gillars at Camp King, Oberursel, Germany, until they conditionally released her on Christmas Eve, 1945. She declined to leave military detention. The United States Justice Department abruptly rearrested her on January 22, 1947, and after detaining her for a year in Frankfort without charging her with any crime, they flew her to the United States on August 21, 1948, to stand trial on charges of aiding the German War effort. She was indicted on September 10, 1948, and charged with ten counts of treason. When her trial began on January 25, 1949, in Washington D.C., prosecutors used just eight of the indictments, focusing their main argument for conviction on the numbers of propaganda programs that the Federal Communications Commission had recorded and her participation in the activities against the United States. The Communications Commission also had evidence that Mildred Gillars had signed an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler. The prosecution also presented testimonies of soldiers and sailors whose stories she had written under false pretenses and twisted for propaganda purposes.

The defense contended that she stated unpopular opinions in her broadcasts, but they did not add up to treason. They also argued that she had been under the influence of Max Otto Koischwitz, and not responsible for her actions until after he died.

Mildred appeared at her trial with a bouquet of bright red roses accenting her less colorful clothing and a black bow tying back her long silver hair. Her attire and attitude resembled a Hollywood premiere instead of a trial for treason. Radio broadcasters and newspaper and magazine reporters from the United States and abroad converged on her trial, including McCall’s and Time Magazine. The Time Magazine reporter covering the trial expressed the popular scorn of the Defenses’ contention that Mildred acted under the influence of Max Koischwitz.

“Little Miss Echo. She described him as a man “who loved the mountains [of Silesia] with the intensity that a man might love a woman.” In 1943 he went there to think about Miss Gillars (he had a wife and three children) and there found that “God favored his love.” After that, she echoed his ideas like an empty barrel on a hog caller’s porch.”

People probably reacted more strongly to Mildred when the prosecution asked her about her relationship with Max Kioschwitz. The Time Magazine reporter wrote, “Miss Gillars lowered her eyes, breathed heavily, and said, “It is difficult to discuss … It is like discussing religion.” But finally, tossing her long silver-grey hair, she admitted, “Of course I loved him.” She added: “I consider Professor Koischwitz to have been my destiny . . .”

On March 10, 1949, the jury found Mildred Gillars guilty of just one count of treason, her action in making the Vision of Invasion broadcast. The judge sentenced her to ten to thirty years in prison, a $10,000 fine in 1949 dollars, with the stipulation of eligibility for parole after ten years in prison. The judge did not impose a harsher sentence since there was no proof that she had taken part in high level Nazi propaganda policy conferences like other American collaborators. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia upheld her conviction in 1950.

Mildred Gillars served her sentence at the Federal Reformatory for Women in Alderson, West Virginia, becoming eligible for parole in 1959. She did not apply for parole until 1961, and she was released on June 10, 1961. While serving her prison time, Mildred had converted to Catholicism, and after her release she went to live at the Our Lady of Bethlehem Convent in Columbus, Ohio. The church operated St. Joseph Academy where she taught German, French, and Music. Fifty-one years later in 1973, she returned to Ohio Wesleyan University and completed her degree, earning a Bachelor of Arts in speech.

On June 25, 1988, Mildred Gillars died of colon cancer at Grant Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio. She is buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Lockbourne, Franklin County, Ohio.

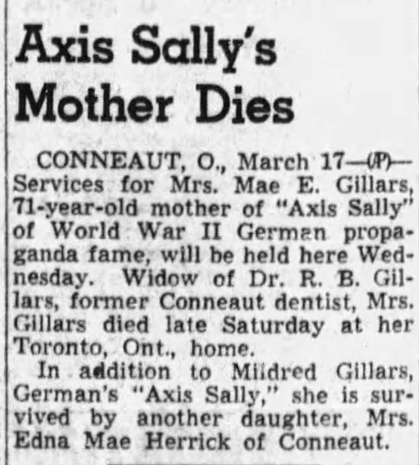

Mildred’s mother, step father and half sister are buried in Glenwood Cemetery, in Conneaut. Mary (Mae) E. Gillars died in March 1947/

Thirty-six years after her death, the life of Mildred Gillars is still controversial and still resonates in today’s pollical and social climates. Writer and short-wave radio enthusiast Richard Lucas believes that Mildred Gillars was neither totally a traitor to her country nor totally innocent in her choices. “I was really trying to have a nuanced story of her and make her seem like a human being rather than a caricature,” says Richard Lucas. “Especially today. People are not black and white; there are all kinds of tradeoffs that lead them to become who they are.”

Was she a premediated traitor who had a deep-seated, long-lasting hatred of America and its ideals or was she a situational traitor with an overpowering need for attention and validation, who made poor choices of men and based her decisions on her feelings for them instead of moral and patriotic reasons?

Sources

Joseph Blundo. Sally’s Axis of Evil Ended at Convent in Columbus. Columbus Dispatch, archived from the original on January 21, 2013.

Axis Sally Brought Hot Jazz to the Nazi Propaganda Machine. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/axis-sally-and-art-propaganda-180970327/

Le Bijou, yearbook of Ohio Wesleyan University, 1922.

Records, Ancestry.com

Find a Grave, Mildred Gillars

Richard Lucas. Axis Sally, the American Voice of Nazi Germany. Casemate, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010.

Example of Axis Sally’s Hot Jazz

Saturday Evening Post Digital Archive – Axis Sally https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=46F25mtF8kg

Gillars’ wartime broadcasts and trial : the 2021 legal drama American Traitor: The Trial of Axis Sally

The Kent Stater, Volume XXIII, Number 32, 25 November 1947. Let’s Face It, Democracy Takes a Beating. https://dks.library.kent.edu/?a=d&d=tks19471125-01.2.16&e=——-en-20–1–txt-txIN——-

“TREASON: True to the Red, White & Blue”. Time. March 7, 1949.