Getting to Know the Great Lakes

Deseronto, Ontario, Canada

Welcome to Octagon Ohio History, brought to you from the David Cummins Octagon House in Conneaut, Ohio. Ashtabula County and all of Ohio has a fun and fascinating history, so let’s explore it together. Our view from the cupola gives us a bird’s eye view of the state and we can peek into all aspects of its history. Come along for an exciting history adventure!

Queen Anne’s Communion Service

Mohawk native tribes had settled the Mohawk Valley in what later would become New York State long before Europeans arrived in the New World in the late 15th Century.

In the seventeenth century, the Jesuits and later missionaries from the Church of England introduced the Mohawks to Christianity. In 1710, a delegation of Mohawk chiefs traveled to the Court of Queen Anne in England with a special mission. They informed Queen Anne that they wished to become Christians and the Queen arranged for a chapel to be built for the Mohawk people at Fort Hunter in the Mohawk Valley in New York.

In 1712, the Queen gave them an eight-piece silver communion set for their new chapel.

After seventy years of peaceful Mohawk worship in the Chapel, the Revolutionary War broke out in the British Colonies in 1775. The Mohawk congregation buried the Queen Anne Communion set at Fort Hunter to keep it safe from looting. The Mohawks remained steadfastly Loyalist during the war, and when the Treaty of Paris ended it in 1783, they were angry and alarmed to discover that the new American government considered them Rebels and had made no arrangements to return their ancestral lands in New York to them.

Mohawk chiefs John Deserontyon, Joseph Brant, and other representatives from the Six Nations presented their case to Frederick Haldimand, Governor General of the Province of Quebec, who encouraged them to settle on Lake Ontario’s northern shore. Chief Brant chose to settle along the Grand River, but Chief Deserontyon and his people chose to relocate along the Bay of Quinte. Before he left the new United States, Chief Deserontyon returned to Fort Hunter and dug up the silver communion service.

On May 22, 1784, Chief Deseronto and about 100 Mohawks arrived west of the modern Deseronto and they held a flag raising ceremony and rededicated the silver communion service to their new country. Eventually, the pioneering Mohawk settlers built new churches and new communities, St. Paul’s in Brantford, and St. Georges in Tyendinaga. Meanwhile, the victorious Americans had used the Queen Anne Chapel as a tavern and stable. They eventually tore it down and used its stones to line the first Erie Canal. More spiritually minded Americans recovered a few of the stones and sent them to the two Anglican churches in Canada.

The wooden Anglican church built in 1784 and located in Tyendinaga Mohawk Territory on the Bay of Quinte sheltered the silver communion service until a new brick church was built in 1843. A historical landmark sign on the original site, serves as a reminder of the collaboration between the British Crown, Ontario’s First Nations, and the Mohawk Loyalist emigres from the new United States of America.

The Mighty Mac

Ferries across the Straits of Mackinac separating Michigan’s Upper and Lower Peninsula had a capacity of about 462 cars per hour and it took them an hour to cross the Straits.

Designed by David Steinman and completed in November 1957, the “Mighty Mac” replaced the ferries that had operated since 1923.

Construction on the Mighty Mac began in 1954 and it is an amazing engineering accomplishment. David Steinman and his fellow bridge builders designed and built the bridge to withstand enormous ice pressure and to be absolutely stable even in hurricane force winds and storms that sweep the Straits of Mackinac. The Mighty Mac is a suspension bridge, five miles long. The outside lanes are 12 feet wide; the inside lanes are 11 feet wide; the center mall is two feet wide, and the catwalk, curb and rail width are three feet on each side, totaling 54 feet. The stiffening truss width in the suspended span is sixty-eight feet wide making it wider than the roadway it supports.

The one hundred millionth crossing of the bridge occurred on June 25, 1998.

November is the Cruelest Month

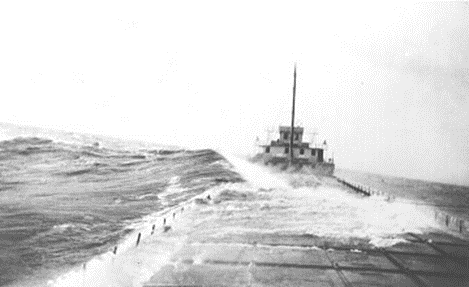

When cold Arctic winds start chilling the Great Lakes, skippers, mates, and ship hands yearn for the end of the shipping season and getting home before the big freeze.

But there is always one more run, just one more big load to make the season and collect that sizeable bonus.

Often in November when sudden storms and wintry ice work together, profit overpowers wisdom and the longing for home, and the captain sails into uncertain waters and races the weather. Savage autumn storms test all sections of a ship. A poorly balanced cargo, weak superstructure, unseen hull fractures…any flaw can be fatal. The fierce gales and wintry blasts of November quickly shred the canvas and shatter the masts. Hundreds of wooden ships and scores of steel ships rest in the icy deep, defeated by November on the Great Lakes.

The modern era of high safety standards, strict loading regulations, radar, and satellite weather forecasting greatly reduce November ship disasters, but ships that challenge November on the lakes still bet with risky odds.

Canoeing the Great Lakes

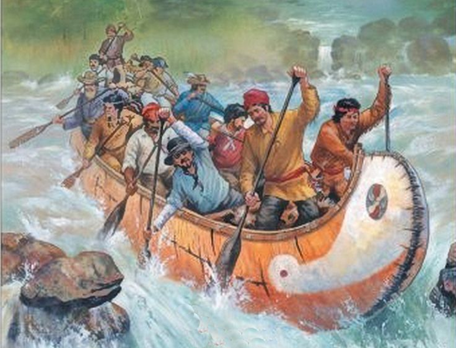

For nearly three hundred years, the simple birch bark canoe has shaped the history of the Great Lakes as an important transportation and practical commercial tool.

The Algonquin Indians were among the first tribes to use the birchbark canoes in what is now the northeastern United States and Canada. Birchbark canoes ranged from about 15 to 20 feet long to about one hundred feet long for some of the war canoes. The canoes carried goods, fishermen, hunters, and warriors. At times, twenty paddlers would navigate the war canoes.

Most Great Lakes Native American tribes were skilled birch bark canoe builders and operators. They used birch bark for the outer skin, reinforced it with cedar wood ribs sewn together with small roots of spruce trees, and sealed with pine gum. This method produced a strong and durable birch bark canoe.

French trappers, explorers, and missionaries valued these canoes as the most practical way of carrying supplies on rivers and creeks. Birch Bark canoes also encouraged them to eventually use the Great Lakes as highways. Canoes could navigate the streams and rivers threading their way through the vast timbered wilderness that separated Montreal from the western lakes and in time voyage from Lake Ontario all the way to Lake Superior.

Many French canoes measured over thirty feet long and often carried an eight-man crew. They could and often did carry a cargo of furs and provisions weighing over 6,000 pounds. The French and English settlers used these sturdy canoes well into the early 1800s.

Journey to Cathay(Now Known as China)

In 1634, Samuel de Champlain, Governor of New France, sent an expedition to the west with the goal of finding furs, charting unexplored land, and discovering a new route to the Orient, specifically Cathay (China). Expedition leader Jean Nicolet voyaged westward to the Lake Michigan shores, landing near Green Bay where Native Americans greeted him in a strange dialect. Believing he had reached China, Nicolet wore Oriental robes to greet what he believed were Chinese people.

Jean Nicolet soon discovered that the population was not Chinese, but residents of Winnebago Indian country, now Wisconsin. He had the background and experience to deal with the situation. Born in France, he had immigrated to Quebec and earned varied experience with Native American tribes. His experience included living with an Indian tribe on Allumette Island in the Ottawa River, learning the Algonquian language and culture and participating in negotiations with the Iroquois. Later he lived with the Nipissing tribe, eventually becoming their interpreter. In 1629, he went to the Three Rivers settlement in New France, becoming the colony’s official interpreter.

Early in 1634, Nicolet and his expedition embarked on their search for China.

They headed westward into Huron territory where he secured a large canoe and with seven Huron tribesmen, they padded down Lake Huron to the Straits of Mackinac into Lake Michigan and to Green Bay. Drawing on his extensive experience with Native American tribes, Jean Nicolet immediately took charge of the situation, arranging for future fur trade with the Winnebago and claiming the new territory for the French North American Empire.

Topky Brother’s , Ship’s Chandlers

W. Peerless, Superior, & Champion Mowers and Reapers, with all the latest improvements. For Sale by H.J. Topky.

Tiger Self-Operated Sulky Hay Rake, and Revolving Hay Rakes, for Sale by H.J. Topky.

Nuts, glass, hooks, latches, screws, bolts, hammers, planes, saws, hatchets, adzes, all carpenter’s tools and building materials, paints, oils, putty, turpentine, etc.etc. by H.J. Topky.

Ashtabula Telegraph

July 20, 1877

Oliver Topky later joined his father and brother John in operating the Topky hardware store in Ashtabula Harbor. Topky Hardware soon became a designated destination in Ashtabula city and township. An 1886 full page advertisement in the Marine Review of Cleveland shows that Topky operated as a ship chandler, a shop selling items for ships and boats, as well as a hardware store. After John died in 1898 and their father Henry Joseph Topky died in 1901, Oliver continued the business with the help of his staff. Mr. Topky finally retired from the hardware business in 1964.

The hardware store was a business when the harbor had a booming shipping trade. Goods were sold by the carload for use on the lake boats. As Mr. Topky recalled, only sailboats were able to enter the harbor and they were towed by tugs. Because the harbor was too shallow for steamboats, a tug had to go on before ships to dredge sand out of their path.

As a vintage Ashtabula Harbor businessman, Oliver Topky remembered many of Ashtabula’s firsts involving ships and railroads. He knew the names and stories of some of the first ships in the harbor, including the Tempest, the Ashtabula, Joshua R. Giddings, Arctic, Mary Collins, and Plow Boy. He could tell tales of the Great Lakes Engineering Company which launched the Steamer Louis R. Davidson in 1912, as its first ship in its Ashtabula yards.